| 1 | | = Architecture = |

| 2 | | |

| 3 | | Our model of authorization in the DETER Federation Architecture (DFA) is that principals are granted the right to perform operations on other principals bases on attributes of the principals. Possession of a given attribute by the requesting principal allows the requested operation to proceeed. The attribute required is set by the principal being operated on. The notions of principals, attributes and negotiation comes from the [http://www.isso.sparta.com/research_projects/security_infrastructure/abac_overview.html ABAC system], which we use as an implemenation. |

| 4 | | |

| 5 | | ABAC provides us with flexible delegation, provable access decisions on which the participants agree, and scalability. The provable decisions can be logged for auditing and correct operations while the scalability properties are key to large deployment. |

| 6 | | |

| 7 | | We review the basic ABAC notions and operations, as well as the DFA operations, and then discuss how that architecture is connected to the DFA. |

| 8 | | |

| 9 | | == ABAC Fundamentals == |

| 10 | | |

| 11 | | ABAC allows us to prove principals have attributes that have been attested to by other principals. We lay out the basic functions here. |

| 12 | | |

| 13 | | === Principals === |

| 14 | | |

| 15 | | Principals are the players in the authorization system. They have a unqiue identity in the system (though a single real world entity may act as several principals in the system), can prove that identity and can make assertions about attributes. Principals in the DFA are identified by their [FeddAbout#GlobalIdentifiers:Fedids fedid]. Within the authorization framework, fedids can be used to sign create credentials as well. |

| 16 | | |

| 17 | | Principals cause actions in the system by requesting operations on other principals. The two principals communicate in such a way that they are certain of one another's identity, and negotiate the access by reasoning about the attributes of the requester. The simplest way to do this is a mutually authenticated interactive connection, but other store and forward sorts of operation are also possible, as long as the two can authenticate the operation request and carry out a negotiation. |

| 18 | | |

| 19 | | Authentication is a binding of a request to a requesting principal about which the object principal can then reason. Many forms of authentication are possible here, and we intend to support as many as possible. The goal of authentication is to bind the request to a principal (i.e., their [FeddAbout#GlobalIdentifiers:Fedids fedid]). |

| 20 | | |

| 21 | | === Attributes and Credentials === |

| 22 | | |

| 23 | | Attributes are asserted about a principal by a principal. Each principal defines its own namespace of attributes, though for principals to agree on how to reason using them they must agree on the semantics of the relevant subset of each others attributes. We generally use a dotted notation of the form `Principal.attribute` to represent an attribute. Attributes are free-form strings (without dots) that are chosen to have some meaning. The principal is the [FeddAbout#GlobalIdentifiers:Fedids fedid] of the principal in question, though in these examples we will replace it with a string representing the principal's role in the discussion. One could imagine a principal representing the DETER testbed defining an attribute `user` that means that any principal about which that is asserted is a user of the testbed. Such an attribute would be referred to as `DETER.user` where `DETER` is a shorthand for the testbed's fedid. |

| 24 | | |

| 25 | | Binding an attribute directly to a principal is done by issuing an assertion signed by the principal whose namespace the attribute is in; such an assertion is called a ''credential''. The simplest credentials are direct bindings of attributes to principals, and are statements digitally signed using a key bound to the fedid. The X.509 attribute certificate is suitable for implementing a credential. |

| 26 | | |

| 27 | | Credentials also represent delegations, as described [http://groups.geni.net/geni/wiki/TIEDABACModel elsewhere]. These delegations are also straightforward encodings of these assertions, signed by the principal controlling the namespace of the deduced attribute. If the DETER principal asserts that all Emulab users are DETER users, that credential is signed by the DETER principal. |

| 28 | | |

| 29 | | While a delegation credential usually represents some kind of agreement or mutual understanding between principals, the creation of the credential needs only the signer's input. When the DETER testbed creates a credential that asserts that all `EMULAB.user`s are `DETER.users`, that credenital can be created without the knowledge of the EMULAB principal, and does not depend on the existence of even one user with the `EMULAB.user` attribute. |

| 30 | | |

| 31 | | Credentials may be issued with lifetimes. Once a credential expires, it is no longer valid and can no longer be used to reason about authorization decisions. |

| 32 | | |

| 33 | | Once a credential is created, it is valid fairly independent of the generating principal. (It is fairly independent only because validating the signature on the credential requires getting sufficient information to validate the signature, which may involve contacting the signer, though in need not.) They are generally passed to those principals that can make use of them, and may even be published. |

| 34 | | |

| 35 | | It is worth noting that some credentials embody information about a principal or the policies of a principal that are not generally known, nor are they intended to be. The ABAC authorization model has provisions for controlling how principals release credentials to others, including securely establishing preconditions on that release. This fact constrains both the number of parties to a negotiation and the system used to find credentials. |

| 36 | | |

| 37 | | === Negotiation === |

| 38 | | |

| 39 | | Negotiating access is the cooperative process of proving to the principal being operated on that the requesting principal has the proper attribute or attributes. The negotation can be characterized as creating a directed graph from requesting principal to principal being operated on where each link is a valid credential. It is a cooperative process because either principal can contribute to the creation of the graph. |

| 40 | | |

| 41 | | While the overall goal is to create the path from required attribute to requesting principal, the negotaition may include proving intermediate attributes in order to release information that one party or the other considers sensitive. For example, a requesting principal may only reveal information about its US governemnt clearances to a principal that can prove it represents the a part of the government with the rights to see the clearance government. This models the sort of behavior where a citizen may not show identification except to a law enforcement official. |

| 42 | | |

| 43 | | Once the negotiation has completed, both parties share the complete reasoning path used to grant access and know the same things about one another. If subordinate negotiations have occurred, that information can be cached and used for later interactions as well. For example, once a principal has been shown to represent a relevant US government body, later interactions can dispense with the data exchange necessary to release such information. |

| 44 | | |

| 45 | | Because such proofs are constructed of valid credentials, they inherently contain validity times. These can be used to determine when or if proofs must be renegotiated or and when derived attributes are no longer valid. |

| 46 | | |

| 47 | | The ABAC negotiation takes place between two parties, but the credentials used to build the proof may come from other principals. Such a third party credential may be issued by an identity validating service, such as a US state granting a driver's license. There are two ways such credentials can enter the negotiation: one party may hold the credential generated by a third party or a thrid party may hold the credential. When one of the negotiating parties enters an thrid party credential into the exchange, it does so subject to the same kinds of controls as any of its credentials, i.e., the party may require an intermediate proof that the other negotiator is qualified to see the credential. Credentials held by third parties (as opposed to credentials issued by third parties) may also be brought into the discussion, but only if those credentials are available without controls. That is to say, negotiators may collect published credentials as part of the negotiation. |

| 48 | | |

| 49 | | This may initially appear to be an odd restriction, but it is tied to the fact that all parties to the negotiation agree on the final proof. In order to acquire information from the third party, one of the negotiators may need to reveal information to th ethird party that it is unwilling to reveal to the other negotiator. The third party and the two negotiators would have different views of the overall state that led to the authorization and would be unable to log the complete justification for the access denial or acquisition. US consumers find themselves in this situation when they attempt to make purchases that require a credit report; the seller is often authorized to see the credit report that the buyer does not have a copy of. Such a case is frustrating in real life, but violates the property that negotiators agree on state in ABAC. |

| 50 | | |

| 51 | | == The DFA == |

| 52 | | |

| 53 | | The DFA builds experiments for researchers from resources acquired from various testbeds (also called federants). Conceptually, this is accomplished by presenting the federator (called {{{fedd}}}) with an experiment description which the federator breaks into sub-experiments that it creates on federants and connects to make the unified federated experiment. The federator negotiates local access with individual testbeds and uses their local configuration language to create and connect the sub-experiments. |

| 54 | | |

| 55 | | === Federator Decomposition === |

| 56 | | |

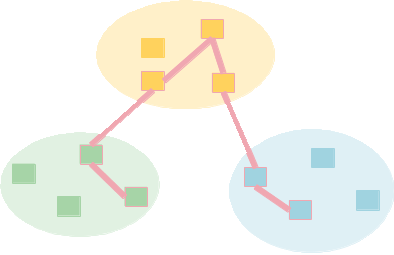

| 57 | | It is helpful both conceptually and practically, to think of {{{fedd}} as having two parts, the ''experiment controller'' and the ''access controllers''. The experiment controller interacts with researchers to create, configure, and manipulate the federated experiment as a whole. It is concerned with acquiring access from federants, decomposing experiment descriptions and manipulations of the global experiment allocation state (deallocating, reallocating, restarting, etc). The access controller is the interface to local resources. It negotiates access to the underlying local resources, maps permissions in the global attribute space into local configurations and credentials, and manages local resources. |

| | 1 | = Authorization Architecture = |

| | 2 | |

| | 3 | |

| | 4 | The Deter Federation Architecture (DFA) builds experiments for researchers from resources acquired from various testbeds (also called federants). Conceptually, this is accomplished by presenting the federator (called `fedd`) with an experiment description which the federator breaks into sub-experiments that it assigns on federants. The federants create the sub-experiments and connect them to make the unified federated experiment. The federator negotiates local access with individual testbeds and uses their local configuration language to create and connect the sub-experiments. |

| | 5 | |

| | 6 | == Federator Decomposition == |

| | 7 | |

| | 8 | The federator as has two parts, the ''experiment controller'' and the ''access controllers''. The experiment controller interacts with researchers to create, configure, and manipulate the federated experiment as a whole. It is concerned with acquiring access from federants, decomposing experiment descriptions and manipulations of the global experiment allocation state (deallocating, reallocating, restarting, etc). The access controller is the interface to local resources. It negotiates access to the underlying local resources, maps permissions in the global attribute space into local configurations and credentials, and manages local resources. |

| 61 | | === Creating an Experiment (pre-ABAC) === |

| 62 | | |

| 63 | | In the pre-ABAC design, allocation decisions on federants were made based on a simple [http://fedd.isi.deterlab.net/trac/wiki/FeddAbout#GlobalIdentifiers:Three-levelNames three-attribute system] where all attributes were attested by a testbed associated with the experiment controller. This was a generalization of the Emulab project/user model extended to include testbeds as a third attribute. |

| 64 | | |

| 65 | | Building a federated experiment consists of gathering access to federants, and allocating resources to the experiment, and initializing the shared environment. Once the resources are allocated and initialized, it is identified by a fedid, which is communicated to the researcher. |

| 66 | | |

| 67 | | A researcher initiates the process by asking a {{{fedd}}} - specifically its experiment controller - to create the experiment. The {{{fedd}}} and researcher mutually authenticate using their fedids. At this point the experiment controller determines from the fedid if the user is permitted to create experiments. This is a simple identity-based decision. |

| | 12 | == Access Control Decisions == |

| | 13 | |

| | 14 | A federant makes access control decisions based on the unique identity of the researcher making the request and a collection of attributes about that researcher. The DFA identifies each researcher by a unique fedid, described below, and attaches a three-level set of attributes, called a three-level name, to each researcher. Specifically, each researcher is assigned three-level names by the experiment controller making the request. |

| | 15 | |

| | 16 | A researcher has only one fedid, but may have several three-level names, where each three-level name represents different roles or attributes that the experiment controller knows about the researcher. Each three-level name is presented in turn to access controllers when gaining access. |

| | 17 | |

| | 18 | Three-level names are a generalization of the Emulab project/user model extended to include testbeds as a third attribute. |

| | 19 | |

| | 20 | === Global Identifiers: Fedids === |

| | 21 | |

| | 22 | In order to avoid collisions between local user names the DFA defines a |

| | 23 | global set of names called DETER federation IDs, or more concisely |

| | 24 | fedids. A fedid has two properties: |

| | 25 | |

| | 26 | * An entity claiming to be named by a fedid can prove it interactively |

| | 27 | * Two entities referring to the same fedid can be sure that they are referring to the same entity |

| | 28 | |

| | 29 | An example implementation of a fedid is an RSA public key. An entity |

| | 30 | claiming to be identified by a given public key can prove it by |

| | 31 | responding correctly to a challenge encrypted by that key. For a large |

| | 32 | enough key size, collisions are rare enough that the second property |

| | 33 | holds probabilistically. |

| | 34 | |

| | 35 | We adopt public keys as the basis for DFA fedids, but rather than tie |

| | 36 | ourselves to one public key format, we use subject key identifiers as |

| | 37 | derived using method (1) in RFC3280. That is, we use the 160 bit SHA-1 |

| | 38 | hash of the public key. While this allows a slightly higher chance of |

| | 39 | collisions than using the key itself, the advantage of a single |

| | 40 | representation in databases and configuration files outweighs the |

| | 41 | increase in risk for this application. |

| | 42 | |

| | 43 | ==== Making a Fedid Certificate ==== |

| | 44 | |

| | 45 | Each `fedd` and client encodes an fedid in an X.509 certificate. The `openssl` command installed on most Unices can create such a certificate. The simplest things to do is the following: |

| | 46 | |

| | 47 | {{{ |

| | 48 | $ /usr/bin/openssl req -text -newkey rsa:1024 -keyout key.pem -nodes -subj /CN=users.isi.deterlab.net -x509 -days 3650 -out cert.pem |

| | 49 | $ cat key.pem cert.pem > fedd.pem |

| | 50 | }}} |

| | 51 | |

| | 52 | The resulting `fedd.pem` file contains an unencrypted private key and certificate. To use a password, the sequence is: |

| | 53 | |

| | 54 | {{{ |

| | 55 | $ /usr/bin/openssl req -text -newkey rsa:1024 -keyout key.pem -nodes -subj /CN=users.isi.deterlab.net -x509 -days 3650 -out cert.pem |

| | 56 | $ openssl rsa -in key.pem -des3 -out keyout.pem |

| | 57 | # Prompts for a password |

| | 58 | $ cat keyout.pem cert.pem > fedd.pem |

| | 59 | $ rm key.pem |

| | 60 | }}} |

| | 61 | |

| | 62 | == Global Identifiers: Three-level Names == |

| | 63 | |

| | 64 | In Emulab, projects are created by users within projects and those |

| | 65 | attributes determine what resources can be accessed. We generalized |

| | 66 | this idea into a testbed, project, user triple that is used for access |

| | 67 | control decisions. A requester identified as ("DETER", "proj1", |

| | 68 | "faber") is a user from the `DETER` testbed, `proj1` project, user `faber`. |

| | 69 | Testbeds contain projects and users, projects contain users, and users |

| | 70 | do not contain anything. |

| | 71 | |

| | 72 | Parts of the triple can be left blank: ( , ,"faber") is a user named faber |

| | 73 | without a testbed or project affiliation. |

| | 74 | |

| | 75 | Because three-level names are the attribute convention used by the DFA, they can represent any 2-level attribute hierarchy that an experiment controller and an access controller agree on. In current practice, most DETER federants continue to use the project/user semantics. |

| | 76 | |

| | 77 | Though the examples used above are simple strings, the outermost (i.e., leftmost) non-blank field of a name must be a fedid to be valid, and are treated as the entity asserting the name. Contained fields can either be fedids or local names. This allows a testbed to continue to manage its namespace |

| | 78 | locally. |

| | 79 | |

| | 80 | If DETER has `fedid:1234` then the name (`fedid:1234`, "proj1", "faber") |

| | 81 | refers to the DETER user `faber` in `proj1`, if and only if the requester |

| | 82 | can prove they are identified by `fedid:1234`. Note that by making |

| | 83 | decisions on the local names a testbed receiving a request is trusting |

| | 84 | the requesting testbed about the membership of those projects and names |

| | 85 | of users. |

| | 86 | |

| | 87 | Testbeds make decisions about access based on these three level names. |

| | 88 | For example, any user in the "emulab-ops" project of a trusted testbed may |

| | 89 | be granted access to federated resources. It may also be the case that |

| | 90 | any user from a trusted testbed is granted some access, but that users |

| | 91 | from the emulab-ops project of that testbed are granted access to more |

| | 92 | kinds of resources. |

| | 93 | |

| | 94 | These three level names are used only for testbed access control. All |

| | 95 | other entities in the system are identified by a single fedid. |

| | 96 | |

| | 97 | === Accessing Federants === |

| | 98 | |

| | 99 | Building a federated experiment consists of gathering access to federants, and allocating resources to the experiment, and initializing the shared environment. Once the resources are allocated and initialized, the resulting federated experiment is identified by a fedid, which is communicated to the researcher. |

| | 100 | |

| | 101 | A researcher initiates the process by asking a `fedd` - specifically its experiment controller - to create the experiment. The `fedd` and researcher mutually authenticate using their fedids. At this point the experiment controller determines from the fedid if the user is permitted to create experiments. This is a simple identity-based decision. |

| | 163 | |

| | 164 | |

| | 165 | Our model of authorization in the DETER Federation Architecture (DFA) is that principals are granted the right to perform operations on other principals bases on attributes of the principals. Possession of a given attribute by the requesting principal allows the requested operation to proceeed. The attribute required is set by the principal being operated on. The notions of principals, attributes and negotiation comes from the [http://www.isso.sparta.com/research_projects/security_infrastructure/abac_overview.html ABAC system], which we use as an implemenation. |

| | 166 | |

| | 167 | ABAC provides us with flexible delegation, provable access decisions on which the participants agree, and scalability. The provable decisions can be logged for auditing and correct operations while the scalability properties are key to large deployment. |

| | 168 | |

| | 169 | We review the basic ABAC notions and operations, as well as the DFA operations, and then discuss how that architecture is connected to the DFA. |

| | 170 | |

| | 171 | == ABAC Fundamentals == |

| | 172 | |

| | 173 | ABAC allows us to prove principals have attributes that have been attested to by other principals. We lay out the basic functions here. |

| | 174 | |

| | 175 | === Principals === |

| | 176 | |

| | 177 | Principals are the players in the authorization system. They have a unqiue identity in the system (though a single real world entity may act as several principals in the system), can prove that identity and can make assertions about attributes. Principals in the DFA are identified by their [FeddAbout#GlobalIdentifiers:Fedids fedid]. Within the authorization framework, fedids can be used to sign create credentials as well. |

| | 178 | |

| | 179 | Principals cause actions in the system by requesting operations on other principals. The two principals communicate in such a way that they are certain of one another's identity, and negotiate the access by reasoning about the attributes of the requester. The simplest way to do this is a mutually authenticated interactive connection, but other store and forward sorts of operation are also possible, as long as the two can authenticate the operation request and carry out a negotiation. |

| | 180 | |

| | 181 | Authentication is a binding of a request to a requesting principal about which the object principal can then reason. Many forms of authentication are possible here, and we intend to support as many as possible. The goal of authentication is to bind the request to a principal (i.e., their [FeddAbout#GlobalIdentifiers:Fedids fedid]). |

| | 182 | |

| | 183 | === Attributes and Credentials === |

| | 184 | |

| | 185 | Attributes are asserted about a principal by a principal. Each principal defines its own namespace of attributes, though for principals to agree on how to reason using them they must agree on the semantics of the relevant subset of each others attributes. We generally use a dotted notation of the form `Principal.attribute` to represent an attribute. Attributes are free-form strings (without dots) that are chosen to have some meaning. The principal is the [FeddAbout#GlobalIdentifiers:Fedids fedid] of the principal in question, though in these examples we will replace it with a string representing the principal's role in the discussion. One could imagine a principal representing the DETER testbed defining an attribute `user` that means that any principal about which that is asserted is a user of the testbed. Such an attribute would be referred to as `DETER.user` where `DETER` is a shorthand for the testbed's fedid. |

| | 186 | |

| | 187 | Binding an attribute directly to a principal is done by issuing an assertion signed by the principal whose namespace the attribute is in; such an assertion is called a ''credential''. The simplest credentials are direct bindings of attributes to principals, and are statements digitally signed using a key bound to the fedid. The X.509 attribute certificate is suitable for implementing a credential. |

| | 188 | |

| | 189 | Credentials also represent delegations, as described [http://groups.geni.net/geni/wiki/TIEDABACModel elsewhere]. These delegations are also straightforward encodings of these assertions, signed by the principal controlling the namespace of the deduced attribute. If the DETER principal asserts that all Emulab users are DETER users, that credential is signed by the DETER principal. |

| | 190 | |

| | 191 | While a delegation credential usually represents some kind of agreement or mutual understanding between principals, the creation of the credential needs only the signer's input. When the DETER testbed creates a credential that asserts that all `EMULAB.user`s are `DETER.users`, that credenital can be created without the knowledge of the EMULAB principal, and does not depend on the existence of even one user with the `EMULAB.user` attribute. |

| | 192 | |

| | 193 | Credentials may be issued with lifetimes. Once a credential expires, it is no longer valid and can no longer be used to reason about authorization decisions. |

| | 194 | |

| | 195 | Once a credential is created, it is valid fairly independent of the generating principal. (It is fairly independent only because validating the signature on the credential requires getting sufficient information to validate the signature, which may involve contacting the signer, though in need not.) They are generally passed to those principals that can make use of them, and may even be published. |

| | 196 | |

| | 197 | It is worth noting that some credentials embody information about a principal or the policies of a principal that are not generally known, nor are they intended to be. The ABAC authorization model has provisions for controlling how principals release credentials to others, including securely establishing preconditions on that release. This fact constrains both the number of parties to a negotiation and the system used to find credentials. |

| | 198 | |

| | 199 | === Negotiation === |

| | 200 | |

| | 201 | Negotiating access is the cooperative process of proving to the principal being operated on that the requesting principal has the proper attribute or attributes. The negotation can be characterized as creating a directed graph from requesting principal to principal being operated on where each link is a valid credential. It is a cooperative process because either principal can contribute to the creation of the graph. |

| | 202 | |

| | 203 | While the overall goal is to create the path from required attribute to requesting principal, the negotaition may include proving intermediate attributes in order to release information that one party or the other considers sensitive. For example, a requesting principal may only reveal information about its US governemnt clearances to a principal that can prove it represents the a part of the government with the rights to see the clearance government. This models the sort of behavior where a citizen may not show identification except to a law enforcement official. |

| | 204 | |

| | 205 | Once the negotiation has completed, both parties share the complete reasoning path used to grant access and know the same things about one another. If subordinate negotiations have occurred, that information can be cached and used for later interactions as well. For example, once a principal has been shown to represent a relevant US government body, later interactions can dispense with the data exchange necessary to release such information. |

| | 206 | |

| | 207 | Because such proofs are constructed of valid credentials, they inherently contain validity times. These can be used to determine when or if proofs must be renegotiated or and when derived attributes are no longer valid. |

| | 208 | |

| | 209 | The ABAC negotiation takes place between two parties, but the credentials used to build the proof may come from other principals. Such a third party credential may be issued by an identity validating service, such as a US state granting a driver's license. There are two ways such credentials can enter the negotiation: one party may hold the credential generated by a third party or a thrid party may hold the credential. When one of the negotiating parties enters an thrid party credential into the exchange, it does so subject to the same kinds of controls as any of its credentials, i.e., the party may require an intermediate proof that the other negotiator is qualified to see the credential. Credentials held by third parties (as opposed to credentials issued by third parties) may also be brought into the discussion, but only if those credentials are available without controls. That is to say, negotiators may collect published credentials as part of the negotiation. |

| | 210 | |

| | 211 | This may initially appear to be an odd restriction, but it is tied to the fact that all parties to the negotiation agree on the final proof. In order to acquire information from the third party, one of the negotiators may need to reveal information to th ethird party that it is unwilling to reveal to the other negotiator. The third party and the two negotiators would have different views of the overall state that led to the authorization and would be unable to log the complete justification for the access denial or acquisition. US consumers find themselves in this situation when they attempt to make purchases that require a credit report; the seller is often authorized to see the credit report that the buyer does not have a copy of. Such a case is frustrating in real life, but violates the property that negotiators agree on state in ABAC. |

| | 212 | |