| | 36 | |

| | 37 | === Negotiation === |

| | 38 | |

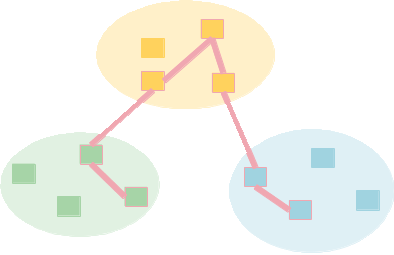

| | 39 | Negotiating access is the cooperative process of proving to the principal being operated on that the requesting principal has the proper attribute or attributes. The negotation can be characterized as creating a directed graph from requesting principal to principal being operated on where each link is a valid credential. It is a cooperative process because either principal can contribute to the creation of the graph. |

| | 40 | |

| | 41 | While the overall goal is to create the path from required attribute to requesting principal, the negotaition may include proving intermediate attributes in order to release information that one party or the other considers sensitive. For example, a requesting principal may only reveal information about its US governemnt clearances to a principal that can prove it represents the a part of the government with the rights to see the clearance government. This models the sort of behavior where a citizen may not show identification except to a law enforcement official. |

| | 42 | |

| | 43 | Once the negotiation has completed, both parties share the complete reasoning path used to grant access and know the same things about one another. If subordinate negotiations have occurred, that information can be cached and used for later interactions as well. For example, once a principal has been shown to represent a relevant US government body, later interactions can dispense with the data exchange necessary to release such information. |

| | 44 | |

| | 45 | Because such proofs are constructed of valid credentials, they inherently contain validity times. These can be used to determine when or if proofs must be renegotiated or and when derived attributes are no longer valid. |

| | 46 | |

| | 47 | The ABAC negotiation takes place between two parties, but the credentials used to build the proof may come from other principals. Such a third party credential may be issued by an identity validating service, such as a US state granting a driver's license. There are two ways such credentials can enter the negotiation: one party may hold the credential generated by a third party or a thrid party may hold the credential. When one of the negotiating parties enters an thrid party credential into the exchange, it does so subject to the same kinds of controls as any of its credentials, i.e., the party may require an intermediate proof that the other negotiator is qualified to see the credential. Credentials held by third parties (as opposed to credentials issued by third parties) may also be brought into the discussion, but only if those credentials are available without controls. That is to say, negotiators may collect published credentials as part of the negotiation. |

| | 48 | |

| | 49 | This may initially appear to be an odd restriction, but it is tied to the fact that all parties to the negotiation agree on the final proof. In order to acquire information from the third party, one of the negotiators may need to reveal information to th ethird party that it is unwilling to reveal to the other negotiator. The third party and the two negotiators would have different views of the overall state that led to the authorization and would be unable to log the complete justification for the access denial or acquisition. US consumers find themselves in this situation when they attempt to make purchases that require a credit report; the seller is often authorized to see the credit report that the buyer does not have a copy of. Such a case is frustrating in real life, but violates the property that negotiators agree on state in ABAC. |

| | 50 | |

| | 51 | == The DFA == |

| | 52 | |

| | 53 | The DFA builds experiments for researchers from resources acquired from various testbeds (also called federants). Conceptually, this is accomplished by presenting the federator (called {{{fedd}}}) with an experiment description which the federator breaks into sub-experiments that it creates on federants and connects to make the unified federated experiment. The federator negotiates local access with individual testbeds and uses their local configuration language to create and connect the sub-experiments. |

| | 54 | |

| | 55 | === Federator Decomposition === |

| | 56 | |

| | 57 | It is helpful both conceptually and practically, to think of {{{fedd}} as having two parts, the ''experiment controller'' and the ''access controllers''. The experiment controller interacts with researchers to create, configure, and manipulate the federated experiment as a whole. It is concerned with acquiring access from federants, decomposing experiment descriptions and manipulations of the global experiment allocation state (deallocating, reallocating, restarting, etc). The access controller is the interface to local resources. It negotiates access to the underlying local resources, maps permissions in the global attribute space into local configurations and credentials, and manages local resources. |

| | 58 | |

| | 59 | Federants will use one of our existing plug-in access controllers or create their own in order to join the federation. The access controller can be physically implemented near the testbed it manages or can be colocated with the experiment controller. To a great extent this decision depends on the level of control that a federant's administrator wants over the access policies and the level to which the testbed resources can be configured remotely. We have demonstrated access controllers that are loosely and tightly bound to their testbeds. |

| | 60 | |

| | 61 | === Creating an Experiment (pre-ABAC) === |

| | 62 | |

| | 63 | In the pre-ABAC design, allocation decisions on federants were made based on a simple [http://fedd.isi.deterlab.net/trac/wiki/FeddAbout#GlobalIdentifiers:Three-levelNames three-attribute system] where all attributes were attested by a testbed associated with the experiment controller. This was a generalization of the Emulab project/user model extended to include testbeds as a third attribute. |

| | 64 | |

| | 65 | Building a federated experiment consists of gathering access to federants, and allocating resources to the experiment, and initializing the shared environment. Once the resources are allocated and initialized, it is identified by a fedid, which is communicated to the researcher. |

| | 66 | |

| | 67 | A researcher initiates the process by asking a {{{fedd}}} - specifically its experiment controller - to create the experiment. The {{{fedd}}} and researcher mutually authenticate using their fedids. At this point the experiment controller determines from the fedid if the user is permitted to create experiments. This is a simple identity-based decision. |

| | 68 | |

| | 69 | Based on the researcher's authenticated identity, the controller knows which three-level names are valid for this user and will present them to the various testbeds to request access (from their access controllers). These three-level names are all based on a local configuration, and this testbed cannot assert three-level names from another testbed, because testbeds are identified by their fedid. |

| | 70 | |

| | 71 | As each access controller gets the request, accompanied by a three-level name, it determines how that name maps to its local access control and tells the requesting experiment controller what access is granted. This process binds the three-level name to the local access control; Emulabs map to a user/project pair, DRAGON maps to an X.509 certificate. |

| | 72 | |

| | 73 | After the access is negotiated, allocation of the local experiment proceeds based on the local credentials at each federant. |

| | 74 | |

| | 75 | == ABAC and the DFA == |

| | 76 | |

| | 77 | In mapping ABAC onto the DFA, three key issues arise: |

| | 78 | |

| | 79 | * Mapping principals into system actors |

| | 80 | * Mapping local access control requirements into ABAC attributes |

| | 81 | * Authenticating principals during operations |

| | 82 | |

| | 83 | We consider each of these in turn. |

| | 84 | |

| | 85 | === Principals in the DFA === |

| | 86 | |

| | 87 | Principals in the DFA possess a [FeddAbout#GlobalIdentifiers:Fedids fedid], which is the basis for their assignment of attributes, though we may bind a specific request to a principal using other means than the fedid. In particular, the following entities are principals in the DFA: |

| | 88 | |

| | 89 | Researchers:: |

| | 90 | A catch-all category for human beings requesting federated services. |

| | 91 | Experiment controller:: |

| | 92 | The {{{fedd}}} component that assembles federated experiments |

| | 93 | Access controllers:: |

| | 94 | The {{{fedd}}} components responsibile for controlling access to testbeds and creating local sub-experiments |

| | 95 | Federated Experiments:: |

| | 96 | The experiment itself |

| | 97 | Sub-experiments:: |

| | 98 | The local allocations of resources by different testbeds |

| | 99 | Testbeds/Federants:: |

| | 100 | The administrators and operators that grant privileges to researchers |

| | 101 | Other third parties:: |

| | 102 | Federants are a particular case of these. Any agency or individual whose vioce is represented in access control decisions is a principal. |

| | 103 | |

| | 104 | Researchers and the controllers are obvious cases of entities that need to be principals. In the simplest understanding of operating on experiments, those are the entities that talk to one another. |

| | 105 | |

| | 106 | Making the experiment itself a principal creates an important point of delegation. |